So the other day, I spent 45 minutes on the phone placing an order that should’ve taken three. That’s what happens when you start messing around with snakes and rattlesnake roundups. You think it’s going to be simple. But it never is.

Now if you live somewhere out in the wilds of Kansas or Oklahoma—or even Texas, though they tend to do everything louder down there—you might appreciate my friend Tom K. He was on the other end of the line. Tom’s a biology teacher by trade, and a rattlesnake wrangler by some kind of cosmic joke. He’s the kind of man who could identify a liver fluke before breakfast and still get the coffee brewing on time.

I met Tom at a rattlesnake roundup—which, yes, is a real thing. And no, it’s not just a myth or something you read about in Field & Stream between the ads for deer urine and waterproof socks. It’s a gathering of folks in belt buckles big enough to fry eggs on, who spend their free time wandering around the prairie, poking under rocks, and hoping the rock doesn’t poke back.

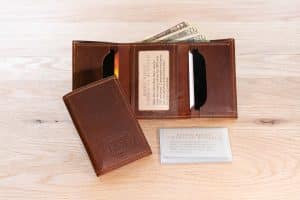

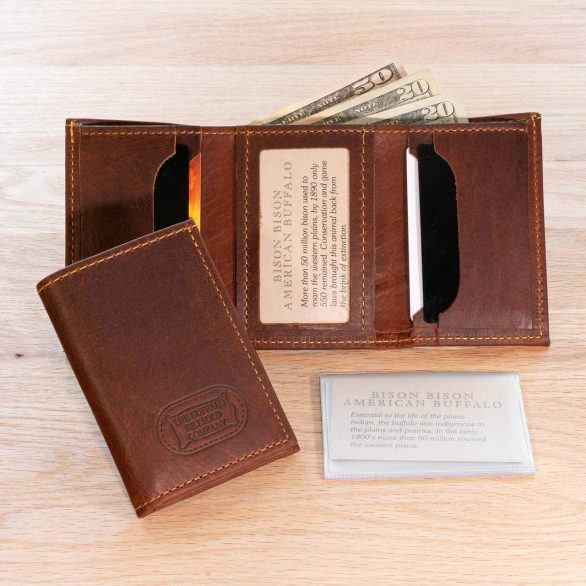

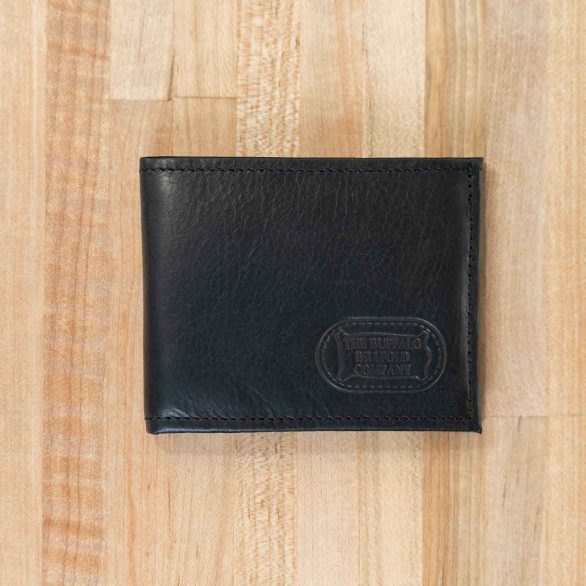

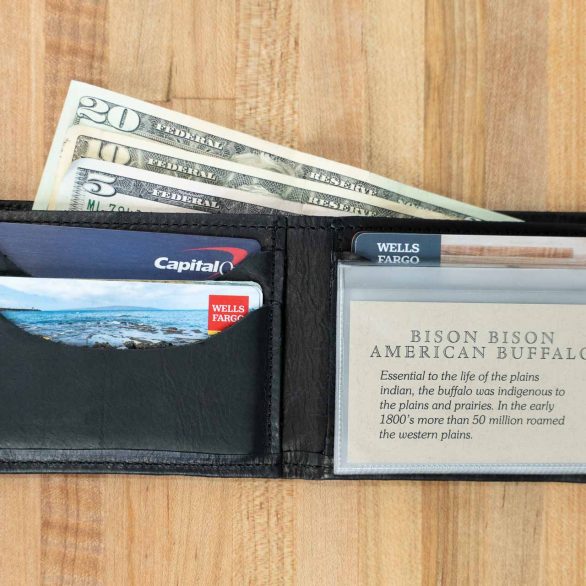

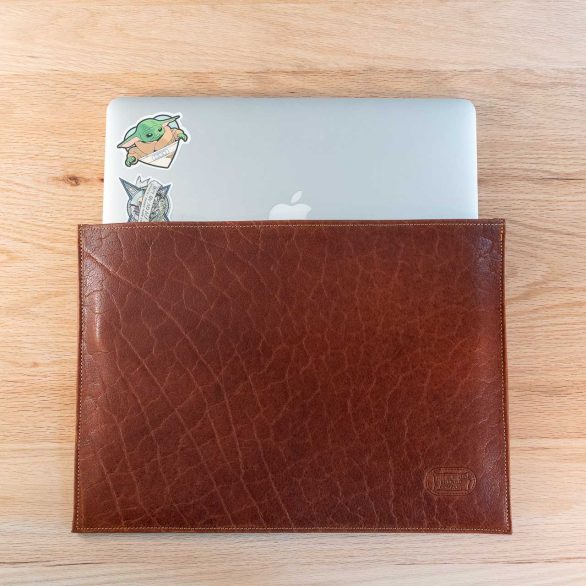

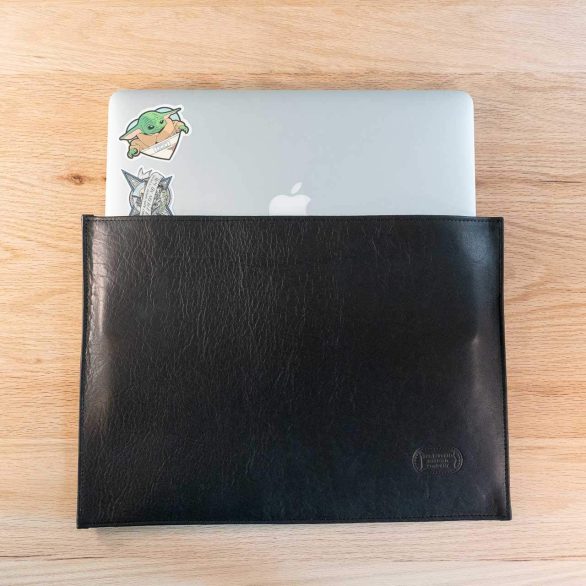

In my line of work, I make leather goods. From leather wallets to guitar straps, maybe a belt if I’m feeling traditional. And sometimes, for a little flair, I appliqué a business card-sized piece of rattlesnake skin to the front of a wallet. I’ve seen a lot of leather goods in my day, and think Rattlesnake skin and Bison leather look quite nice together, ‘specially on that guitar strap. And handling a rattlesnake wallet makes a man feel like a bit of a desperado every time he buys a cup of coffee.

Now don’t go getting your undies in a knot. These snakes aren’t coming out of the Garden of Eden. They’re coming from places where ranchers are trying to protect horses—because nothing sours a stallion’s mood faster than stepping on a coiled-up diamondback.

Tom attends these roundups all over the country. He’s got a pickup that’s seen more back roads than a Bible salesman and enough coolers to start his own convenience store. He’ll bid on the whole lot—sometimes two thousand pounds of snakes—and if he’s lucky, he drives home with a trailer full of what looks like the world’s most aggressive spaghetti.

I buy between 350 and 500 feet of rattlesnake skin from him every year. That’s a snake a block and a half long, which is the kind of math you only do if you’re making things from snakes—or you’re stuck in traffic and wondering why your life took this particular turn.

Tom is a wizard when it comes to tanning Crotalus atrox—that’s Latin for “diamondback rattlesnake,” but saying it in Latin helps people take it more seriously. We’ve tried many tanners…Tom is the best.

Now, at these rattler roundups, you get a whole spectacle: food stands, funnel cakes, families, and a stage where a guy in a cowboy hat will hold a six-foot snake like it’s a new kind of jump rope. Thousands of people show up to see the devil hiss in public. I went once. It was… memorable. I haven’t felt the need to go again.

Anyway, when it’s all over, Tom ends up with hundreds—literally hundreds—of live rattlesnakes, ranging from “respectable” to “biblically terrifying.” He stores them in giant freezers like he’s preparing for a snake-based apocalypse.

Most are beheaded and skinned on site. The skins go to folks like me. The meat—yes, rattlesnake meat—is sold to vendors out west. And sometimes the venom gets harvested for anti-venom, which is ironic, since it’s like making lemonade out of landmines.

This last roundup took place in a small Oklahoma town where the sidewalks were new back when Herbert Hoover was still sending telegrams. The WPA poured concrete and hope into the place, but time and tree roots have lifted the sidewalks into little concrete waves that are almost suitable for surfing….if they were water. The town used to have two thousand people and a hundred trains a day. Now it’s got about a thousand people and maybe four good knees among them.

And that’s where Tom got bit.

Yes, after processing a six-foot rattler—skinned, presumed safe—the snake’s nervous system did what God designed it to do. Five minutes after dying, it bit clean through Tom’s finger. You’d think the worst part of owning a thousand rattlesnakes is feeding them. It’s not. It’s getting bit by one that’s technically already dead.

They had to call in a helicopter because the closest medical care was a three day journey by mule, and they were fresh out of mules. People think a chopper ride costs twenty grand. That’s cute. Try doubling that, then doubling it again.

The Oklahoma wind got wild, and the pilot had to make an emergency landing. An ambulance met them, ferried Tom the rest of the way. By the time he got to the hospital, they’d already inked lines up his arm to track the venom—like a very painful game of connect-the-dots. Every time the swelling crossed a new mark, they gave him another $10,000 dose of anti-venom. That went on for half a day. You do the math, but maybe sit down first.

By morning, the doctors decided to let him keep his finger. Swollen like a bratwurst in July, but still attached. A year later, it aches when the weather turns. That’s biology for you—always reminding you of your mistakes.

He’s intending to refuse the “Ivory Fang Award” at next year’s roundup. That’s a real thing they give to people who get bit. Tom declined. He said he doesn’t glorify foolishness, and that’s why he’s a teacher.

We ended our phone call after forty-five minutes of rattlesnake talk. He’s sending me eighteen snake hides, each four to five feet long. I got his blessing to tell you this story.

And so I have.

Life’s strange, isn’t it?

One minute you’re ordering leather, the next you’re calculating the velocity of venom. But that’s the way it goes, out here where the sidewalks buckle, the rattlers still strike, and the best stories take just a little longer than they should.

Great story, Bill.

I’ve had one of your rattlesnake billfolds for a few years now! Love it! Wears well! Buying my son one.

Great story!!