In my little shop, tucked away in Worthington where the wind blows steady and the coffee’s always close by, I’ve found that a conversation is rarely just small talk. Folks come in, and I ask the usual:

Where are you from? What brings you to our little corner of the prairie? How did you find us, and what possessed you to wander this far?

That’s never boring. Never. It’s how stories begin.

This morning a gentleman by the name of Cork Zylstra walked through the door. Now that name, “Zylstra,” it rings with a good Dutch thunk. You hear it and you know there’s history behind it—maybe some stubbornness, maybe a knack for clean fences and neat ledgers. But I digress.

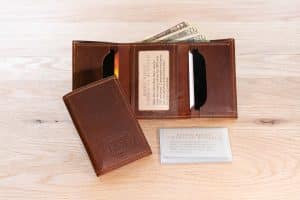

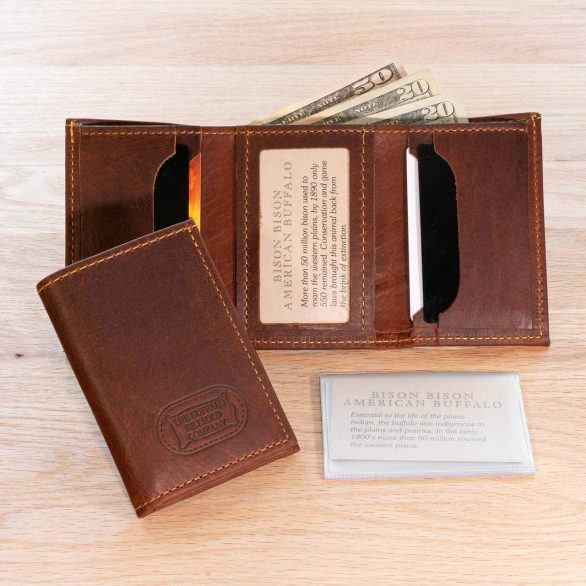

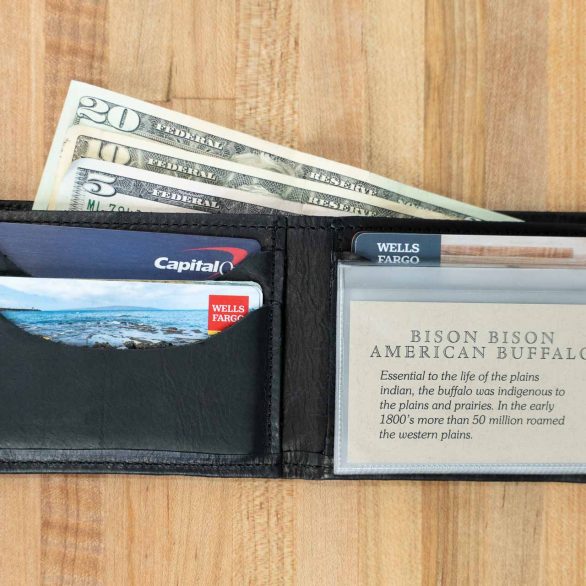

Cork wasn’t here just to pass the time. He came in to replace an old Buffalo Billfold belt, one that had clearly survived both time and sun, and perhaps more than a few adventures. It looked like it had been worn through several governments and at least one monsoon.

So I asked him, as I always do, “What’s your story?”

Turns out, Cork spent the better part of his life flying over Africa—not metaphorically, not in the poetic sense, but literally, up in the clouds, ferrying people across jungles, deserts, and savannahs in a commercial cockpit. Nairobi, Sudan, South Africa—places most of us know only from maps or National Geographic specials.

He’s got a home now on the shores of Lake Victoria in Tanzania. Imagine that: your front porch looking out on a lake bigger than some countries, with hippos grunting in the reeds and the sky so wide it makes your chest ache.

He told me stories—like how he flew dignitaries and professionals into corners of the continent that most folks wouldn’t venture into without divine intervention or hazard pay. The man lived the kind of life that makes Out of Africa look like a tourist’s scrapbook.

Now, Cork’s in his eighties. He’s grounded, sure, but not idle. He still works with airplanes—C-130s, the kind of aircraft that look like they were built by folks who meant business. They’re used now for something remarkable: hauling endangered wildlife across the continent.

Picture this:

Eight or ten rhinoceroses—great gray beasts with skin like armored luggage—loaded gently into the belly of a cargo plane, their horns dulled, their eyes closed, headed off to safer lands.

Or, maybe more astonishing yet—hundreds of tranquilized serval cats. Not in cages. Not packed in like freight. Just resting side by side, laid out with the care of Sunday linens. Their ears long as legend, their legs spindly and built for pouncing, watched over by a team of calm, steady veterinarians who make sure the cats don’t wake up mid-flight and start asking questions.

Meanwhile, back here in Worthington, I know folks who haven’t crossed the county line since the Eisenhower administration. Good people, salt-of-the-earth—but you meet a man like Cork, and you realize: there are entire lifetimes being lived far beyond our field of vision.

It brought to mind a line from Mark Twain, who knew a thing or two about traveling and listening:

“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness… Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth.”

And Cork Zylstra, well—he’s lived the opposite of vegetating. His life could be mistaken for fiction if he hadn’t walked into my shop and shook my hand.

I’m humbled. Honored. And grateful.

You never know who’s going to walk through the door.

But if you’re lucky, they might just leave you with a story that hums in your head for the rest of the day.

Bill Keitel

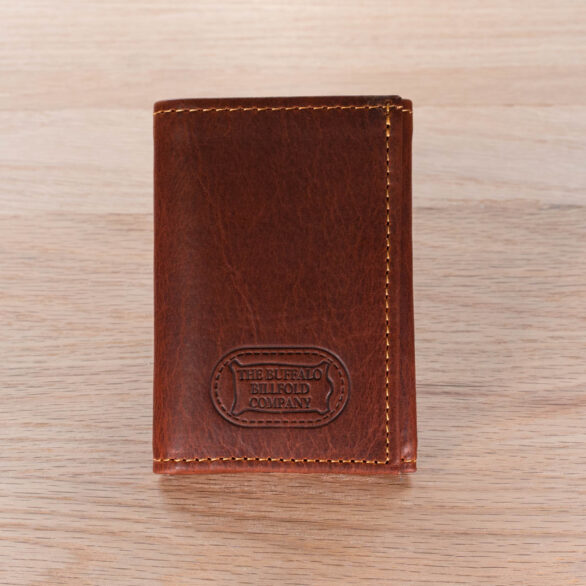

Buffalo Billfold Company

Where the prairie meets the improbable.

Very interesting story I enjoyed reading the story. I leave in Africa and I know cork. And your right Dutch are stubborn hahaha